A new method

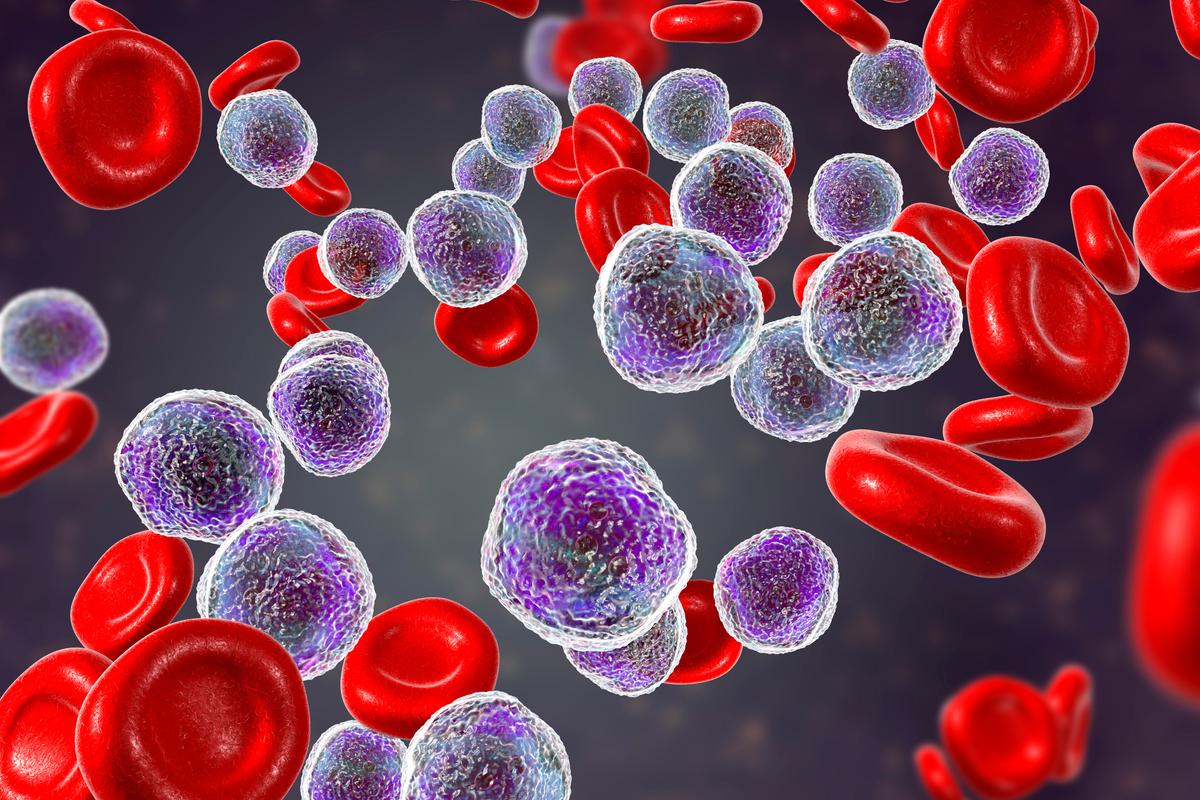

T-cell leukemia is a rare form of leukemia, most prevalent in children but can also occur in adults. Just like any other type of cancer, leukemia is caused by an accumulation of genetic changes ('mutations'), changing the way cells behave and turning them malignant.

In earlier trials, prof. Jan Cools and prof. Kim De Keersmaecker (KU Leuven) discovered that T-cell leukemia cells can harbout 10 to 20 of these genetic mutations, but it was impossible to say whether all leukemia cells had the same mutations or not. With their new research method, the researchers could simultaneously analyse 5,000 individual cells in every blood or bone marrow sample, obtained during diagnosis and during chemotherapy treatments of patients with T-cel leukemia.

To obtain detailed information about every individual cell, the cells are isolated in small droplets that remain separated during the genetic analysis. "This new method to analyse the genetic defects in thousands of individual leukemia cells, enables us to determine differences between cells that all look the same under the microscope," professor Jan Cools says.

Individual cells follow

The researchers examined thousands of individual leukemia cells at diagnosis and at different times during the chemotherapy treatment. New data showed that not all leukemia cells carry the same genetic mutations: for every patient there was typically a large group of leukemia cells with the same mutations that occur together with smaller groups of cells with other mutations. “This is an important realisation”, professor Cools says, “because it gives new insights on how leukemia develops, and this appears more complex than we originally expected.”

By analysing leukemia cells during the treatment, researchers found that most leukemia celles disappear quickly (within 1-2 weeks), but that some cellls with certain genetic mutations were longer detectable.

We can obtain detailed information about which of these leukemia cell are less susceptible to treatment and can possible cause a relapse of the illness.Prof. dr. Heidi Segers, paediatric haematologist-oncologist

"Now that we can follow the individual leukemia cells based on the genetic defects present in each cell, we can obtain detailed information about which of these leukemia cells are less susceptible to therapy and can potentially cause a relapse of the disease," according to prof. dr. Heidi Segers (UZ Leuven) who collaborated to the trial.

The non-profit organisation Kom op tegen Kanker has provided financial support to make this trial possible. Erwin Lauwers, responsible for Project financing of Biomedical Research, explains: “Innovative techniques enable us to map the differences between patients, so that they can be given personalised treatment. Cancer patients with a low risk of relapsing can get less intensive treatment to improve their quality of life, while patients with a high relapse risk can be treated more efficiently to increase their chance of survival. This trial could be the start of a large international collaboration to improve the prognosis and diagnosis of patients with T-cell leukemia.”